“What is the greatest virtue a steam man may have to best fulfill his role?“ The Professor was already going strong before my foot touched the last wrung of the companionway ladder into the engine room.

“I don’t know.”

“A steam man’s greatest virtue is reason and moderation”

“I’m no wiz at math, but that sounds like two virtues to me.”

Budge, unhearing, went on:

“The three essential elements of the steam man’s art is fire, water and air. Only the most equitable balance between them ensures safe operation; and therefore an auspicious outcome to our common endeavor. And what is our common endeavor?”

“To not be blown to smitherines?”

“Yes, for one. And our number one priority.” He went to his blackboard and drew a pyramid.

“The harmonious disposition of the three elements, fire, water and air, is essential for a well-ordered steam engine. These three elements form an equilateral triangle with air at the apex. The dynamic between them produces the miraculous, fourth element, steam.” At the last word, he hit the blackboard so hard the chalk broke. “What would you say is an analogous model in other aspects of life?”

“You have me there Mister Budge.”

“A corresponding relationship exists in the three parts of the human soul: the calculating nature, the spirited nature, and the grasping nature—appetite. Just as the equitable disposition of air, Fire and Water creates the conditions to fuel our ship, so the harmonious accord of the three parts of soul; each doing their part in the appropriate measure and time, ensures the success of our collective enterprise. But it’s essential that all parts be ruled over by the faculty of reason. Disequilibrium among the parts—or elements—would spell disaster.” Here he erased the triangle with a dramatic flourish.

“Mister Spencer, report topside. We are approaching the station. Prepare to take on a passenger.”

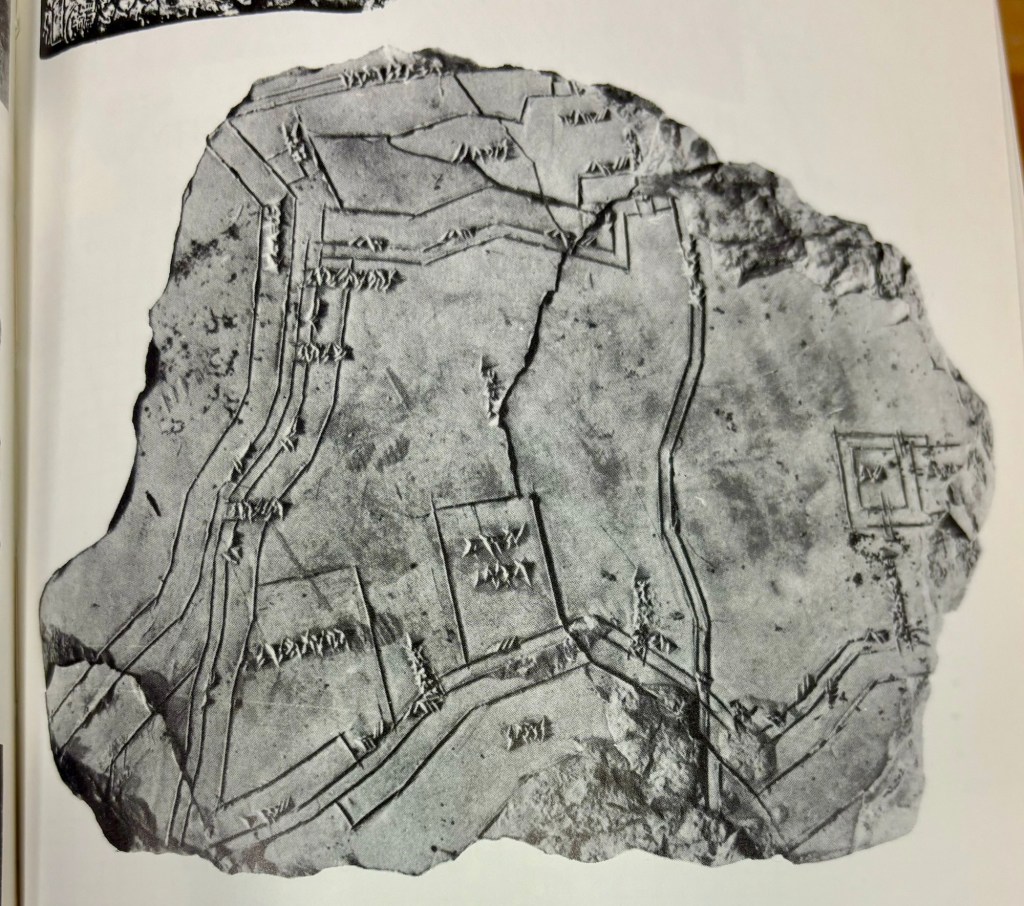

I went into the wheelhouse as we neared the wharf. McWhirr said: “He’s a big shot named Osman Hamdi Bey, director of the Imperial Ottoman Museum. Word is, he’s been a royal pain in the arse in getting authorization for the Dig at Nippur—a real stickler for rules. His reputation for obstinacy is well known to the trustees back in Pennsylvania. There’s rumors about an article he wrote to help his buddy and patron, Midhat Pasha, whitewash the Bulgarian Massacre. He probably wants to check us out to make sure we don’t steal the loot.”

I could hear the revulsion in McWhirr’s voice. There’s nothing he abhors more than man’s inhumanity to man. The massacre was a horrible war crime and had liberals in England all worked up; calling for revocation of British support for the Ottoman Empire. But Osman’s spectacular finds in Syria—and securing them for the Ottoman Imperial Museum—had made him famous. It had also made him anathema to the covetous British Museum officials who were incensed that the treasures should be held in the “barbarous” hands of the Turks. So who is to say what was really behind the outrage at Osman’s alleged role as apologist for brutal treatment of the April Revolutionaries by the Ottoman army?

The landing was covered by an absurdly large pile of luggage attended by two Arab porters. Then a tall, lanky guy in a fez walked slowly up the gangplank with the dignified gate of man of affairs. For all his reputation, he wasn’t much to look at. But he was a real professor, not some bargain, boiler room philosopher like our engineer, Thaddeus Budge.

Osman’s effects were loaded by the porters who, as it turned out, were personal assistants accompanying him aboard for the trip to Nippur. They quickly spread their mats under a striped tarpaulin on the foredeck and set to making coffee over a charcoal stove.

“Welcome aboard, Mister Bey.”

“Thank you, but your kind greeting is redundant. Bey actually means “mister.” Nonetheless, it’s a pleasure to finally meet Saturnius McWhirr. I was pleased to hear that the most august, Pennsylvania Museum board has hired you to ensure the safe transport of our precious antiquities.”

“Your fame precedes you as well, sir. But where, if I may be so bold to ask, are we to stow all your gear? Or should we just chuck it all overboard now in the interests of expediency?”

Osman’s eyes glared from behind his prince Nez glasses. Thus began the strange, unlikely relationship of the two most remarkable men I’ve ever known.