You must give up your personal history.

This terse comment by Carlos Castaneda’s teacher Don Juan, in Journey to Ixtlan, contains the key to this spiritual travelogue in which he renounces his anthropological career to enter the sorcerer’s path.

The drawings done of Castaneda, partially erased by himself, speak more eloquently than revelations of his mendacity or alleged misogyny.

For the sorcerer, reality, or the world we know is only a description.

For novelists (it is absurd to argue which category this work belongs) the world is the reality in which they are immersed at the moment of creation.

My feelings were clear bodily sensations; they did not need words.

Yet he describes, at great length, terrifying encounters in the intermediate realm. When Castaneda is shaken by these experiences, Don Juan commands him:

Write! Write or you’ll die!

It is an imperative Castaneda takes to heart. Abandonment of personal history might contradict Don Juan’s statement about writing as survival but, rather than a bid for immortality, Castaneda’s account may be the final act of self erasure. It resulted, ultimately, in irrelevance. As he progressed to the rank of Nagual (teacher of sorcery), the fiction stylist was displaced by his persona-his double. As he was subsumed into the anemic New-Age genre, he became infatuated by his own image (or its absence) and got mired in convoluted explications of sorcery. Most fatal, he lost his sense of humor.

Unfortunately this seems to be the lot of many successful artists who find endless justification for their surrender to the allurements of the marketplace.

But Journey to Ixtlan is Castaneda in his prime. Take the hilarious scene where Don Juan and his sidekick Don Genaro-as antidote to Castaneda’s attachment to his worldly vehicle-make his car disappear:

“Where’s my car?”

Don Genaro began turning over small rocks and looking underneath them…

“Don Genaro is a very thorough man,” Don Juan said with a serious expression. “He’s as thorough and meticulous as you are. You said yourself that you never leave a stone unturned. He’s doing the same.”

Genaro, puffing and sweating, tries to lift a boulder.

We could not budge the rock. Don Juan suggested we go to the house and find a thick piece of wood to use as a lever…

Resigned to this insanity, Castaneda lends a hand; with a tremendous effort, they lift the boulder.

…Don Genaro examined the dirt underneath the rock with the most maddening patience and thoroughness.

“No. It isn’t here,” he announced.

Other passages are suffused with a beauty as stark and dramatic as the desert landscape through which they travel. In the chapter, Becoming a Hunter, the sophisticated anthropologist, Castaneda, admits to the reader his feelings of superiority over an Indian. Reading his mind, Don Juan says:

“We are not equals. I am a hunter and a warrior and you are a pimp.”

Don Juan then meets Castaneda’s angry protest at these harsh words with a masterful act of “not doing.”

…when it was pitch black around us he seemed to have merged into the blackness of the stones. His state of motionlessness was so total it was if he did not exist any longer.

It was midnight before I realized that he could and would stay motionless there in that wilderness, in those rocks, perhaps forever if he had to. His world of precise acts and feelings and decisions was indeed superior.

I quietly touched his arm and tears flooded me.

Castaneda has been maligned for having done his field-work exclusively in the UCLA library. But, for me, this only makes his work more impressive. No other writer so cannily expressed the manic spirit of the psychedelic era. I am forever astounded by the man who could transmute the dusty anthropological tomes of the UCLA library into supreme works of imagination.

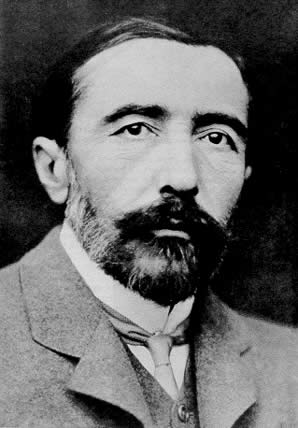

Joseph Conrad started writing relatively late in life. He drew heavily from a long career as master mariner in the era of European, eastern expansion.

Joseph Conrad started writing relatively late in life. He drew heavily from a long career as master mariner in the era of European, eastern expansion.