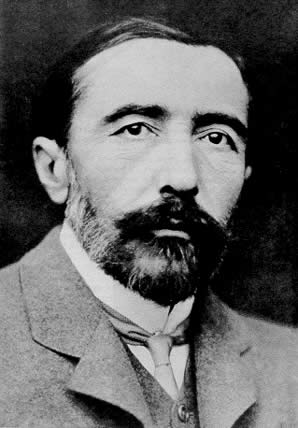

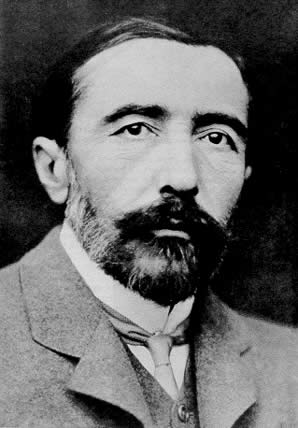

Joseph Conrad started writing relatively late in life. He drew heavily from a long career as master mariner in the era of European, eastern expansion.

Joseph Conrad started writing relatively late in life. He drew heavily from a long career as master mariner in the era of European, eastern expansion.

In A Personal Record he tells of the first impulse to write. Sitting idle in his room at Bessborough Gardens he remembers his initial encounter with the man who inspired his first novel, Almayer’s Folly.

Conrad was 1st mate on a cargo steamer going up a Malaysian river to deliver supplies to a remote outpost. On board was a pony which the Dutch trader, Almayer, has ordered from Bali:

The importation of that Bali pony might have been part of some deep scheme, of some diplomatic plan, of some hopeful intrigue. With Almayer, one could never tell. He governed his conduct by considerations removed from the obvious, by incredible assumptions, which rendered his logic impenetrable to any reasonable person.

The same might be said for the whole colonialist adventure. But this misguided effort is constantly undermined by inscrutable forces antithetical to the rigid mindset of the European.

Conrad describes the limp pony as he hoists it onto the dock in a sling:

…his aggressive ears had collapsed, but as he went slowly swaying across the front of the bridge, I noticed an astute gleam in his dreamy, half-closed eye.

Upon releasing the sling, the pony immediately flattens Almayer and bolts for the dense forest- an outcome which Almayer meets with perplexing indifference.

But Almayer, plunged in abstracted thought, did not seem to want the pony anymore.

He embodies the ambiguous, often childish, desire for dominion over the remotest corners of the earth; a tragi-comic symbol of imperialist hyper-extension who, despite his convoluted plans, succumbs to uncontrollable forces and, ultimately, to dissipation.

Listen to Almayer’s halting, distracted monologue as he reveals to the narrator something of his frustrations:

“…the worst of this country is that one is not able to realize…” His voice sank into a languid mutter. “And when one has very large interests…” He finished faintly. “…up the river.”

Conrad was to later use such chthonic imagery and musical, fractured dialogue in his masterful indictment of imperialism: Heart of Darkness.

A Personal Record tells how the encounter with this “factual” character was instrumental in the birth of a long literary career; a career in which he brought to fictional art an unequaled degree of expressiveness. With the concision of the sea language in which he was so fluent-a language as pithy as poetic verse-Conrad condensed into the microcosmic image of Almayer all the absurdity and hubris of the expansionist age.

Conrad goes on to imagine meeting his alter ego in the Elysian fields and confessing:

It is true, Almayer, that in the world below I have converted your name to my own uses. But that is very small larceny…Your name was common property of the winds…You were always complaining of being lost in the world, you should remember that if I had not believed enough in your existence to let you haunt my rooms in Bessborough Gardens you would have been much more lost.

Though a failure in his wind-born life, Almayer triumphs in the end through Conrad’s belief in the ability of his protagonist to express something deep and dark in the psyche of modern man. This ability is all the more poignant because of Almayer’s fictive power. It is a power that confers reality.

…if I had not got to know Almayer pretty well it is almost certain there would never have been a line of mine in print.

Though I suspect Conrad’s Personal Record may not conform entirely to fact, his character attains a loftier status. He becomes a symbol of human folly that mere veracity cannot express.

Joseph Conrad started writing relatively late in life. He drew heavily from a long career as master mariner in the era of European, eastern expansion.

Joseph Conrad started writing relatively late in life. He drew heavily from a long career as master mariner in the era of European, eastern expansion.